Busy vs. Productive

“What is the gravest crisis facing the American people in the year ahead?”

CBS news asked its panel of “distinguished commentators” that question at the end of 1961.

Most of the answers were predictable, given the era. Most said the Cold War. One said East Berlin would provoke a new military conflict.

Then came Eric Sevareid.

Sevareid was a protege of Edward R. Murrow. He had seen untold global conflict, as the first journalist to cover Paris’s fall to the Nazis.

But Sevareid wasn’t worried about war. He was worried about laziness.

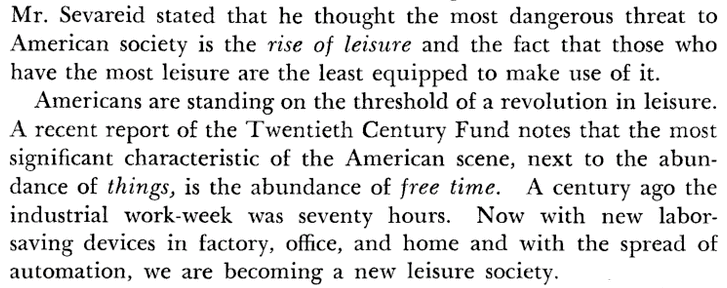

According to CBS:

The idea that leisure was our biggest threat seems absurd fifty years later, when survey after survey shows we feel busier than ever.

About half of Americans say they don’t have the time to do what they want to do, according to Gallup. Three-quarters experience frequent stress. More than half say they are overworked.

But Sevareid was onto something. I think he spotted a problem decades before most people.

Higher productivity has freed up time from the average American’s day. But rather than using that extra time for leisure, or to become even more productive, we’ve used it to become busy.

Busy isn’t the same thing as working hard. Busy is the waste that occurs when you don’t know what to do with the free time that’s fallen into your lap, so you squander it on something unproductive and disappointing.

That’s what Sevareid warned about fifty years ago when he said “those that have the most leisure are the least equipped to make use of it.”

And it’s pretty much what’s happened since.

No matter how busy and overwhelmed people feel today, they have (on average) more leisure time than at any other point in history.

-

We work fewer hours at the office. Average hours worked per year declined from more than 2,000 in 1950 to 1,764 by 2014.

-

We work less at home. Men and women combined spent 36.3 hours a week on household work in 1965, and 27.6 hours per week by 2011, according to Pew Social Trends.

-

We have more leisure time. Leisure time – when you’re not at work or doing housework – has increased from an average of 52 hours per week in 1950 to more than 60 hours today.

This is what you should expect from a world with rising productivity. Computers do in seconds what used to take weeks, washing machines do what used to be done by hand, and email does what used to require face-to-face meetings. It’s crazy to think a world that went from typewriters to fiber optics couldn’t squeeze out a few more hours of freedom out of an average day. And in fact, it did.

But hardly anyone notices.

Despite the increase in leisure hours over the last several decades, the percentage of Americans who say they don’t have enough time in a day has been relatively constant, at about 50%, according to Gallup.

Why?

Dozens of nuanced things are going on. But two stick out to me as playing the biggest role.

1. Technology has pushed the cost of distraction to zero.

I can flip between Twitter, email, a news app, a text message, a Slack conversation, and Facebook, all within a minute.

This is nothing to be proud of.

Technology has freed up time, but it’s also reduced the commitment required for engaging in a task.

When talking to someone required an actual meeting, or when writing something required sitting at a typewriter that could only do one thing, distractions were expensive, as you had to go somewhere else to do something else. But today the cost of distraction is basically zero.

Multitasking was a serious skill when the cost of switching tasks was high. It was rare, so people strived for it.

But multitasking is now effortless. It’s so easy that it’s dangerous – an almost sure path to distraction.

Maybe we feel pressed for time because we’re constantly occupied but not getting much done, with our attention never more than 10 seconds away from checking Twitter. When you try to do 10 things at once, none of them get done very well, and take longer to finish.

Busy, but not productive.

Kanyi Maqubela recently recently said, “Single-tasking is a competitive advantage in this day and age.”

He’s so right.

2. Physical work has a clear start and stop point. Cognitive work never ends.

If your job is to dig a ditch, or sew a shirt, there is a clear distinction between working and not working. But if your job is creating a marketing campaign, or managing a project, or writing software code, the line between work and not work blurs. You’re working with your mind, which is harder to shut off than your arms or your legs.

As the economy shifts from manual labor to “thought” jobs, work increasingly becomes something that people can’t turn off. You may be just as engaged in work making dinner in the evening as you are during a mid-day meeting.

Add to it that many thought jobs require, more than anything else, time to think. Quiet time to let creativity grow, and to think a problem through. But we’re still stuck on the old world where productive work was only what took place when you were doing something, like swinging a hammer.

Since we still equate action with productivity, people spend a big part of their day uselessly engaged in looking busy: Endless meetings, creating deliverables, and generating the appearance of work without making much headway.

If your job requires you to think, but you spend your work day trying to look busy, then your job inevitably comes home with you, since the only quiet time you have to think about work is during what’s supposed to be your after-work leisure time.

Here again, busy but not productive. Just as Sevareid warned.

Years before he became Warren Buffett’s investing parter, a young lawyer named Charlie Munger created a system to manage his time.

Lawyers sell their trade by the hour. Realizing his knowledge of the world would pay dividends throughout his career, Munger blocked off an hour of his work day to read and reflect.

“I decided I would sell myself the best hour of the day to improving my own mind,” he said. “The world could buy the rest of the time. But that hour was mine.”

Not all of us have that much freedom. But the idea that time doesn’t make room in your day – you have to make room for it – is something we should consider.

I feel swamped most days. I wish I had more time to read, walk, and reflect. But I usually feel too busy. Not too productive. Too busy.

When I add up how much time I spend each day checking Twitter, glancing at my phone, reading email, checking a breaking news message … it’s depressing. It may feel like 30 seconds here and a minute or two there. But it adds up to serious time. I’d be less busy and more productive if I sold that time back to myself.

As Munger showed, that takes a concerted effort. It’s not easy. It’s not cheap either – he literally gave up an hour of work per day.

But a lot of us would be better off trying it.

Nassim Taleb says “My only measure of success is how much time you have to kill.” That’s free time to do something productive with, rather than become overwhelmed by with something keeping you busy. It’s the smart way to manage leisure. Sevareid would be proud.