Great Products vs. Great Businesses

In January 2004, when Facebook was a days-old dorm room project, Mark Zuckerberg was asked by a friend whether he thought his social network would make money. “Well I don’t know business stuff,” Zuckerberg responded over IM. “I’m content to make something cool.”

From that moment through today, Facebook’s market cap has increased by $964 per second. So the business stuff worked itself out.

But we have to acknowledge how rare this is. Because the business world is increasingly filled with something that makes me nervous: Great products with little to no sustainable business model backing them, driven by the expectation that, like Facebook, if users enjoy the product enough, sufficient money will follow.

Something that should be more obvious than it is is that the gap between a great product and a great business can be ten miles wide. Often times that gap is correlated: The reason some products become popular is because users aren’t paying a sustainable price for them. They’re getting investor-subsidized services, and of course they like that.

Start with some loose definitions:

-

A product is something that solves someone’s problem.

-

A business is a product that works so well that people will pay more than it costs to produce.

Just separating those out as two different things is important, because while every great business is backed by a great product, not every great product turns into a great business.

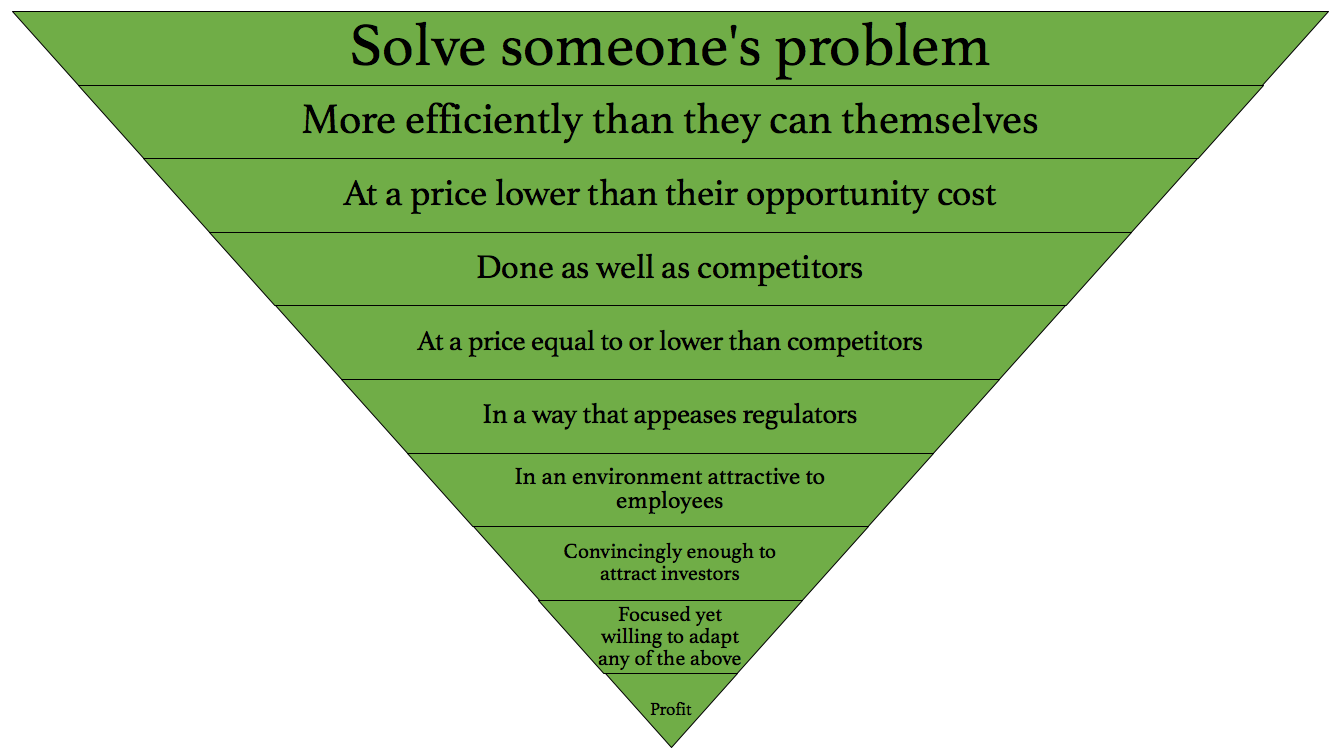

Making a business work requires mastering a series of steps, each one harder than the one before it. I call it the hierarchy of profit:

Great products live in the top few bars of this pyramid. Getting from there to the bottom is incredibly hard. Brent Beshore says building a company is like getting punched in the face while eating glass. It doesn’t happen overnight, and figuring out how to make it work means running losses for a period of time.

But losses come in different flavors. There is a difference between a company that loses money because it’s investing in the infrastructure needed to become a profitable company, and a company that loses money because it can’t charge customers a price that reflects what it costs to run the business. But we often conflate the two, treating all loss-making startups with a sense of, “It’s OK, they’re growing.” (Fred Wilson has a great post on how much burn is reasonable).

When Stitch Fix announced it was going public last month, people were shocked at how strong its financials were. Stitch Fix had profits. It actually asked customers for more money than it cost to run the business. People who study young tech companies were floored:

“Stitch Fix files for IPO… and miraculously, they’re almost profitable.”

“$1B IPO and Profitable…a word rarely seen in any tech company overview.”

“Stitch Fix’s IPO Showcases the Rarest of Unicorn Traits—Profit.”

Stitch Fix should be praised because it’s built an awesome business. Several other startups have done the same: Sweetgreen and Simply Gum come to mind.

But it’s disheartening how unusual this financial success is treated, particularly at companies that are five or more years old.

It’s treated as rare because we – investors, entrepreneurs, journalists – have become too comfortable with companies that make awesome products but don’t have an awesome business. Or any business.

Part of this has to do with how the venture capital industry has evolved in recent years. Companies are staying private longer than they used to. So venture investors that specialize in the early phase of big-losses-because-we’re-investing-in-what-it-takes-to-build-a-profitable-business have found themselves holding mature companies that in a different era would have been passed onto investors who demanded a sustainable business model with profits. In any other era, Uber, Airbnb, Pinterest, and others all would have been public companies by now. And public markets almost certainly wouldn’t let losses pile up for as long as they have. We’ve seen this with Blue Apron and Snap, whose shares have fallen between 50% and 70% since going public just months ago. Both make amazing products that attracted armies of users, which VC investors oogled over. But public investors took one look at their business models and said, “What the hell is this?!” Who knows what that means for their future as standalone companies.

Facebook probably set a bad precedent, giving founders and investors the impression that you should just focus on product and when the time comes all you have to do is flip the advertising switch and poof, you’ll create a money machine. It rarely happens that way. Or anything even close to it. One of my fears is that we’ll look back at the last decade of innovation and realize we were good at making awesome products, but didn’t realize the full potential of those products because we didn’t focus enough on sustaining them with viable businesses.

A common phrase I hear from founders is, “I want to build a company that lasts a generation.” I love it – it’s the perfect attitude. But the best way to fulfill that vision has to be building a great business with the same passion that’s given to building a great product. And that strategy should be implemented early on, ingrained in the company’s culture and viewed as an integral part of controlling your company’s destiny.

This doesn’t have anything to do with appeasing greedy investors. And it doesn’t have anything to do with taking away focus from your product. It’s almost the opposite. Zuckerberg, to his credit, figured this out. When Facebook went public, its S-1 said, “Simply put: we don’t build services to make money; we make money to build better services.”