“Insurance Is Sold, Not Bought.”

In an influential 1979 behavioral economics paper, Daniel Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tversky developed “Prospect Theory” as a way to make sense of decision-making. The summary of the paper was, if I may, that humans do not make optimal decisions, which normative (”should”) frameworks suggest, but instead have irrational aversion to certain losses, and minimize the probability of other losses.

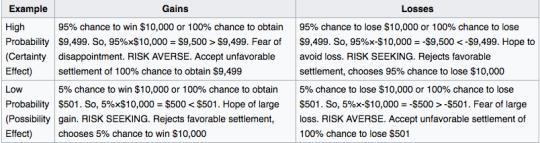

Here’s an example:

Here, Kahneman (via Thinking, Fast and Slow) outlines the cases where a decision-maker irrationally minimizes potential losses versus maximizing potential gains. As the theory goes, humans sometimes choose to be risk-averse, even it results in an unfavorable outcome. The opposite also applies: we sometimes are risk-seeking even if it results in an unfavorable outcome. The intersection of actuarial science and behavioral economics purports to find itself in the bottom right box. You choose to buy insurance, which is $1 more than the statistically-adjusted cost of “going for it” because of the fear of losing $10,000. At least, that’s how the model suggests it would be, right?

It is illegal to drive without auto insurance in all 50 states of the country today. The penalties range per state, but it is on the order of $150 to $1000 for a first offense, and in some states even a month’s imprisonment! And yet, in 2012, 1 in 8 motorists were uninsured.* That number is high enough to suggest that the bottom right quadrant of the matrix above does not apply as cleanly as we would hope it to. Some drivers, of course, flatly can’t afford a monthly payment, or have a risk calculus that combines the risks relating to auto insurance with other financial risks in their lives. That is to say, it’s impossible to know what everybody’s short term financial needs are; walk a mile in another man’s shoes, right? But nonetheless, many drivers are simply risk seeking in a way that breaks even this probability distortion model. Of course, the whole point of prospect theory is that actual decision-making includes a variety of probability distortions and mental shortcuts. And in this case, even when it is mandated by law, with a financial penalty not only for accidents, but also for non-adherence, double digit-percentages of drivers still go without auto insurance. Mental shortcut, indeed. Health insurance, which is (for now) mandated by federal law, has comparable adoption numbers. The uninsured rate for health insurance was 11.9% in 2012.**

The insurance policies that people buy often fall into two categories. One: mandated by law, with scary non-adherence implications; two: mandated as a means to accessing something else you really want, like a house or an apartment. Other than that, many consumers choose to wing it, either because there are short term cash needs which appear more pressing, or because they believe it “wouldn’t happen to them”. These behavioral quirks in our psychology are really important for insurance tech companies to study, and learn well. Insurance tech is very “hot” right now. Many startups are thinking about the great ways that usage-based insurance, flexible and tied to smaller, more granular actions, can be more efficient, empowering, and consumer-friendly. They’re right. But we think we’re safer, healthier, and better protected than we are. So, a caution in designing your business model to account for what will likely be expensive customer acquisition. A caution in designing technocratic policies, especially if you’re going to model consumer behavior. Insurance is sold, not bought.

* http://www.iii.org/fact-statistic/uninsured-motorists

**http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population/?currentTimeframe=0