We’re All Innocently Out of Touch

Seven billion people on this planet share a flaw: They’re out of touch with almost everyone else.

I’m out of touch. You’re out of touch. Neither of us fully understand why so many other people think differently than we do. Look, we try hard. We’re well meaning and open-minded. But as Mark Twain said, “If you hold a cat by its tail you will learn something you can’t learn any other way.” The most important stuff can’t be learned vicariously. You have to experience it. And all of us have wildly different experiences.

We’re just now realizing how wide this chasm of experiences is. The coolest part of the last 10 years is the connecting of different minds through social media. But the more views we’re exposed to, the harder it is to stomach that so many different views exist. Realizing how many different views exist forces you into one of two spots: Arguing with others whose views you think are wrong, or realizing how out of touch you are with people whose experiences have led them to different views. Both are hard to deal with.

This applies to investing.

Your teens and 20s are an important time. You start learning how the economy and the stock market work, and what they’re capable of. Money, like politics, is emotional. And emotional fields tend to be rooted in views formed at a young age.

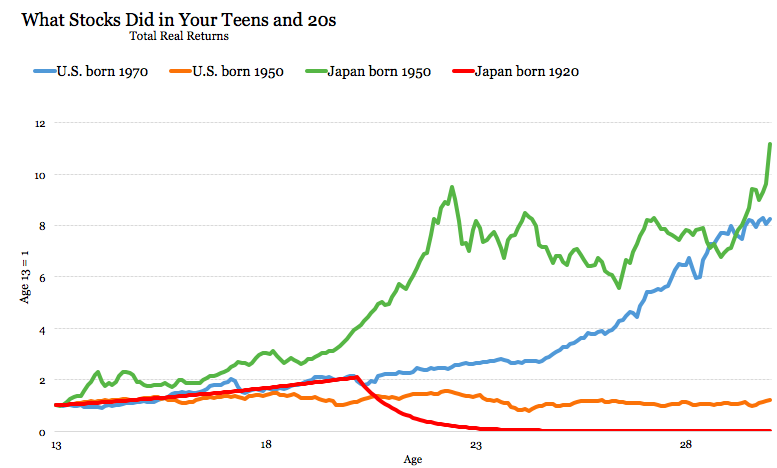

Now, scan different countries and generations, and the range of experiences people had in their youth is a mile wide:

An American born in 1970 saw stocks rise more than eightfold in their teens and 20s. An American born in 1950 saw stocks go nowhere in their teens and 20s. In Japan, the difference between back-to-back generations was losing 100% of your money vs. making 11.5x on your money.

Do you think these groups went through the rest of their lives thinking the stock market was capable of the same thing? Or posed the same risks? Or equally capable at securing a comfortable retirement?

Of course not.

Everyone knows the anecdotes of Great Depression babies never trusting the market again. But there’s hard evidence: A team of economists once crunched generations of data on how people invest. They found wildly different desires to accept investing risk across generations, and those swings coincided with the booms and busts that specific generations experienced, particularly in their youth.

One quote from the study stuck out to me: “Current [investment] beliefs depend on the realizations experienced in the past.”

That’s powerful. Think of the arguments we deal with in investing – over valuation, over expected returns, over moats, over bubbles. Two people with the same education and same data can think bitcoin is either the next tulip or the next internet. The whole reason markets work are because these gaps in opinion exist. But why do they exist, if we all have roughly the same data? Part of it is because we’ve all had different experiences, and current beliefs depend on past experiences. Which means we’re all pretty much out of touch with one another.

Fredrick Lewis Allen, in his book on the 1930s, wrote that Great Depression “marked millions of Americans – inwardly – for the rest of their lives.” But there was a range of experiences. Twenty-five years later, as he was running for president, John F. Kennedy was asked by a reporter what he remembered from the depression, and answered:

I have no first-hand knowledge of the depression. My family had one of the great fortunes of the world and it was worth more than ever then. We had bigger houses, more servants, we traveled more. About the only thing that I saw directly was when my father hired some extra gardeners just to give them a job so they could eat. I really did not learn about the depression until I read about it at Harvard.

This was major point in the 1960 election. How, people thought, could someone with no understanding the biggest economic story of the last generation be put in charge of the economy? It was, by my reading, overcome only by JFK’s experience in World War II. That was the other most important experience of the previous generation, and something his primary opponent, Hubert Humphrey, didn’t have.

The big point is that no amount of studying or listening lets you fully understand what it was like to experience these events. I read a lot of military history, but I will never comprehend what it’s like to be in combat. You can recreate stories, but you can’t recreate fear, adrenaline, and genuine uncertainty. So everyone who has been in combat will always have a different nuanced view about war than I do, no matter how hard I try to put myself in their shoes. The same is true for business, career, and investment history that all of us study.

Four years ago the New York Times did a story on the working conditions of Foxconn, the massive Chinese electronics manufacturer. The conditions are often atrocious. Readers were rightly upset, and many demanded changes. But a fascinating responses to the story came from the nephew of a Chinese worker, who wrote:

My aunt worked several years in what Americans call “sweat shops.” It was hard work. Long hours, “small” wage, “poor” working conditions. Do you know what my aunt did before she worked in one of these factories? She was a prostitute.

The idea of working in a “sweat shop” compared to that old lifestyle is an improvement, in my opinion. I know that my aunt would rather be “exploited” by an evil capitalist boss for a couple of dollars than have her body be exploited by several men for pennies.

That is why I am upset by many Americans’ thinking. We do not have the same opportunities as the West. Our governmental infrastructure is different. The country is different. Yes, factory is hard labor. Could it be better? Yes, but only when you compare such to American jobs.

I don’t know what to make of this. Part of me wants to argue, fiercely. Part of me wants to understand. But mostly it’s a blunt-force example of how different experiences can lead to vastly different views. Views we would never consider at first pass. We’re all out of touch, through no other fault than the random luck of our experiences.

Jeremy Grantham is a well-known investor who has been, with few exceptions, bearish for much of his long career. Why? Many reasons, but this description, from the book Bull!, provides context:

Fresh out of Harvard Business School, Grantham played the go-go market at its peak. By 1970, he had lost all of his money. “I like to say I got wiped out before anyone else knew the bear market started,” Grantham recalled years later.

He lost all of his money during a bull market at the start of his professional career. I didn’t experience that. You probably didn’t, either. But Grantham did. That’s his history. And it likely shaped how he thought about risk for the rest of his life in a way that I’ll never comprehend. He won’t understand my point of view all the same.

Three years ago Michael Sam came out as the first openly gay NFL player. Some were thrilled. Others weren’t. Sportscaster Dale Hansen gave a monologue offering his take and support of Sam: “I don’t understand his world, but I understand that he’s part of mine.”

It’s a totally different issue driven by different causes, but that’s a good framework for business and investing. I don’t have to understand your investing views. But I have to understand that you’re an equally influential part of the economy, and I’ll come closer to understanding your actions by asking what you’ve experienced to make you believe your views, rather than wondering why you don’t agree with mine.

Start with the assumption that everyone is innocently out of touch and you’ll be more likely to explore what’s going on through multiple points of view, instead of cramming what’s going on into the framework of your own experiences. It’s hard to do. It it’s uncomfortable when you do. But it’s the only way to get closer to figuring out why people behave like they do. Which is the puzzle we’re all trying to solve.