Healthcare: What Happens Next

When trying to predict what’s going to happen to the US healthcare system, the safest bet is usually nothing.

It takes a huge shift to register a difference in an industry that accounts for a fifth of our economy. The immediate effects of COVID-19 are vast and unprecedented.

And while many of the adjustments that we’ve made in response to the virus are temporary, we can already see how three major consequences will create lasting changes to how we deliver and pay for healthcare.

1. Overwhelmed the healthcare workforce and supply chain

Frontline healthcare workers were under-resourced and under-staffed from the beginning, as they risked their lives to mitigate the pandemic. Insufficient PPE, testing capacity, etc. left workers exposed, causing them to become sick and hospitals short-staffed. New York had to call in retired providers and the military to fill the gaps. Moreover, the unrelenting stress of triage medicine has driven major increases in PTSD and anxiety among health professionals. We hope to see health systems shift their staffing models to reduce the physical and mental health risks of emergency care.

COVID will change how health systems manage their supply chains. Medical facilities were caught without sufficient inventory (e.g., PPE, ventilators, etc.) and without a reliable supplier to mitigate the gap in time. Most supply chains were built under the assumption that access to overseas manufacturing wouldn’t be disrupted. Going forward, we expect to see health systems prioritize local sourcing and more robust tracking systems to ensure a higher degree of visibility into inventory management.

2. Limited availability of in-person care, accelerating adoption of existing telehealth platforms and threatening the financial position of providers

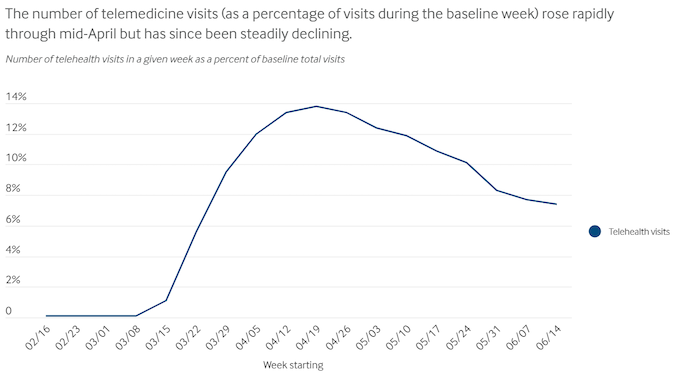

To increase capacity of hospital systems in COVID hotspots, and keep patients and healthcare workers safe, policymakers and providers raced to increase the supply of remote care. The CARES Act removed restrictions on physician licensing and reimbursement for virtual visits, driving utilization of telehealth services to explode up 50-175x year over year.

It’s not yet clear how Congress will expand telehealth coverage or which specialties will stick with remote services long term. But given how satisfied providers and patients are – the majority are interested in continuing to use telehealth on an ongoing basis – we believe widespread use of virtual care is here to stay.

We can start to imagine a healthcare system without physical limitations – one where providers can simultaneously meet with a patient and create the necessary coding and billing documentation for that visit, and patients can receive most of their healthcare out of acute settings.

Burnout was a consistent and growing threat to our healthcare workers even before COVID. Tools that support the highest and best use of provider time can improve providers’ daily workflow and the quality of care. One way of doing this is to create communications platforms with embedded administrative tools. With a growing share of health interactions happening online, each consult is also a record, opening up the potential to automate how providers get compensated (e.g., eligibility verification, billing, claims submission, etc.), reducing provider time spent on charting and administrative work.

The rapid and deadly spread of COVID through nursing homes will increase demand for home-based care as patients and families avoid shared spaces and stricter regulations drive up costs. Pre-COVID, the primary telehealth use case was for more convenient urgent care. Now that so many patients are comfortable with telehealth, there is the potential to deliver routine chronic care management (e.g., for behavioral health conditions, heart disease, etc.) and home health services virtually.

With people skipping elective procedures and check-ups, provider revenue is plummeting at the same time costs of taking care of the hundreds of thousands of COVID patients are exploding.

The American Hospital Association estimates that hospitals and health systems will lose an average of $50.7 billion per month from March-June 2020. This is driving intense cost cutting programs – making it harder than ever for startups to sell into health enterprises – and bankruptcies. To stay alive, some providers will consolidate – join up with other providers or sell to major health plans or health systems.

Fee-for-service providers are hurting especially badly. Without their typical volume of elective procedures, they’re experiencing massive budget shortfalls. Provider groups with value-based care contracts are less susceptible to a severe drop in volume, and are well-positioned to pick up new providers post COVID. Acceptance and coverage of digital services will advance adoption and successful outcomes of value-based care models, in which providers can leverage digital tools to intervene early and save on downstream costs.

3. Changed the way millions of Americans pay for healthcare, shifting people off employer-based insurance to enroll in Medicaid or become uninsured

Last year, the majority of Americans (56%) were on employer-based insurance. As millions of Americans lose their jobs and remain unemployed, there could be 2-3x more uninsured folks in the US for the next several years.

With an influx of people who are uninsured, under-insured, or on Medicaid, there is new opportunity for low-cost, direct to consumer healthcare services, especially for low-acuity conditions. We expect to see the rise of cheap alternatives either through digitally native solutions, or as an addition to an existing retail-focused model (like those we’ve seen in CVS, Walmart, Walgreens already), shifting care out of hospitals to more cost-effective settings.

However, improvements in healthcare services for all low-income populations is long overdue. We’ve known for decades now that a patient’s zip code is one of the most reliable predictors of their life expectancy.

Structural racism in our economy (e.g., inequity in access to quality housing, nutrition, etc.) and our healthcare system creates the conditions for Black and Latinx people to get sick at higher rates and denies them access to affordable treatment. We see this across conditions and geographies. When we look at maternal health outcomes – Black mothers are 3-4 times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white mothers.

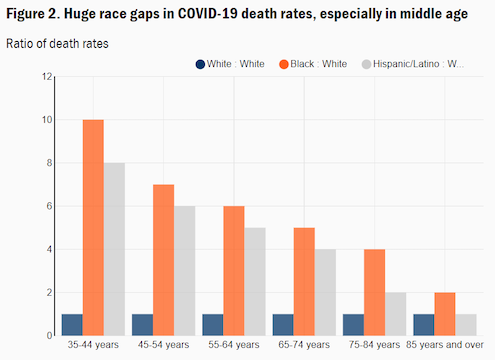

COVID compounds existing health disparities among communities of color, which account for a disproportionate share of our essential workers and have to continue to work in crowded settings, increasing their risk of exposure. These workers often can’t afford to safely social distance, face challenges in accessing testing and treatment, and are more likely to have underlying medical conditions that increase their risk of severe illness. Because of this, Black people are dying at up to 10 times the rate of white people in certain age groups.

As the industry adjusts to care for those affected by the economic crisis, we need to shift resources to solutions that are built to address social determinants of health, which increase risk of death and disease among communities of color, and center racial equity.