Immutable Truths and Arguing Fools

There are a few things that are so obviously true, and true for everyone, that no one argues about them. But most stuff isn’t black or white. Most of the stuff we argue about usually have many truths – several “right” answers depending on the person and situation – and we’re actually arguing over the other person not having the same goals, needs, risks, and wants as you do. It’s a mess. And the only thing worse than thinking everyone who disagrees with you is wrong is the opposite: being persuaded by the advice of those who need or want something you don’t.

This is common in finance. You can count the number of things that are certain on one hand, so the “right” answer to most finance questions is just however much uncertainty you want to accept, which is not only different for everyone but constantly changing for everyone. People don’t agree on a lot of big investing points because they shouldn’t.

Realizing this pushes you towards the few immutable truths, contextualized by your needs, and away from foolishly arguing why two completely different people don’t think the same thing – which is so much of what happens in this industry.

Here’s an extreme example of what I’m talking about.

Stay in school. Work hard. Study. Get good grades.

Almost everyone reading this article agrees with those words. But most reading this article are not grade students in deep poverty. JD Vance was, and writes in his book Hillbilly Elegy:

As a child, I associated accomplishments in school with femininity. Manliness meant strength, courage, a willingness to fight, and, later, success with girls. Boys who got good grades were “sissies” or “fag**ts.” I don’t know where I got this feeling … But it was there, and studies now show that working-class boys like me do much worse in school because they view schoolwork as a feminine endeavor. Can you change this with a new law or program? Probably not. Some scales aren’t that amenable to the proverbial thumb.

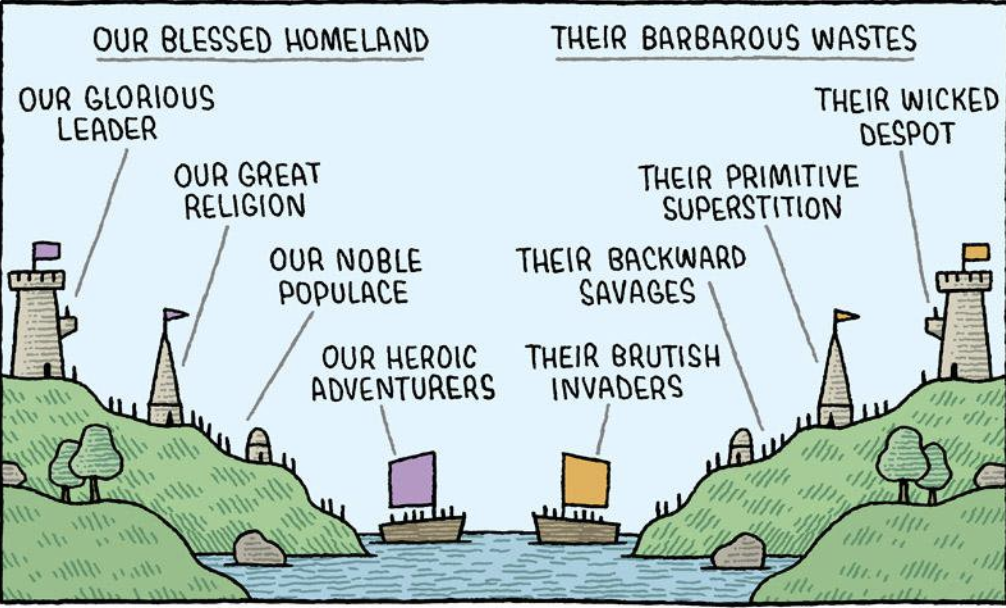

This is so foreign to the world I know. But so is my world to them. I think they’re wrong, but they’d say the same to me. I’m sure I’m right; so are they. Often the reason debates arise is that you double down on your view after learning that opposing views exist.

Here’s another.

Former New York Times columnist David Pogue once did a story about harsh working conditions at Foxconn tech assembly factories in China. A reader sent him a response:

My aunt worked several years in what Americans call “sweat shops.” It was hard work. Long hours, “small” wage, “poor” working conditions. Do you know what my aunt did before she worked in one of these factories? She was a prostitute.

Circumstances of birth are unfortunately random, and she was born in a very rural region. Most jobs were agricultural and family owned, and most of the jobs were held by men. Women and young girls, because of lack of educational and economic opportunities, had to find other “employment.”

The idea of working in a “sweat shop” compared to that old lifestyle is an improvement, in my opinion. I know that my aunt would rather be “exploited” by an evil capitalist boss for a couple of dollars than have her body be exploited by several men for pennies.

That is why I am upset by many Americans’ thinking. We do not have the same opportunities as the West. Our governmental infrastructure is different. The country is different.

Yes, factory is hard labor. Could it be better? Yes, but only when you compare such to American jobs.

If Americans truly care about Asian welfare, they would know that shutting down “sweat shops” would force many of us to return to rural regions and return to truly despicable “jobs.” And I fear that forcing factories to pay higher wages would mean they hire FEWER workers, not more.

Here again, a world completely foreign to my own leading to a debate over something one side assumed was black and white. I could fiercely debate this reader’s response, but I honestly don’t know what to make of it other than it being an example of when you introduce – to any topic – a little social nuance, a little economic variety, a little tribal identity, you’ll get opposing views.

Nothing we debate in investing is as important as those two stories. But so much of what we argue about is influenced by nuance and variety that makes two equally smart people come to different – sometimes opposite – conclusions.

Is this asset cheap? I don’t know. It depends how much time you have and what your stomach for risk is and what factors the broader market considers cheap and what factor future markets will want to bid up for and whether you’ve staked your career on cheap being a good thing. Ask different people and you’ll get different answers because there’s no right answer.

Does this strategy work? I don’t know. It depends what you consider “working” and how quickly your performance will be judged by your boss/client/investors/spouse. Again, there’s no right answer.

Should you care about this forecast? I don’t know. Depends how you’re already invested and how it’ll influence your decisions.

Should you save more? I don’t know. It depends how deeply you want to sleep at night.

Should we cut taxes? I don’t know. It’ll affect different people in different ways.

You can do this for almost every investment topic. The biggest things we argue about have risks, and risk just means the odds of success are less than 100% – either because something might not work for the intended person, or it’ll never work for an unrelated person. That’s why we’re arguing and debating. There are no right answers. I do things with my money that might make you cringe, and vice versa. But if it works for me and what you do works for you, so be it. Life is inconsistent.

We could stop there and it’d be enough. But the most important point here is acknowledging the risk that during your research you’ll be persuaded by the analysis and opinions of people who are different than you.

Maybe they have different timelines, or different needs, incentives, client demands, career/promotion quirks, sales targets, family matters, risk appetites, life experiences, cultural persuasions … on and on. I would never assume a champion bodybuilder’s diet and exercise routine would be appropriate for me. But for some reason the same thing doesn’t translate to finance, and college sophomores watch CNBC to gain insight into a billionaire hedge fund manager’s latest moves.

Turns out it’s hard to put yourself in someone else’s shoes, so the default is to subconsciously assume everyone wears the same ones you are. A group of psychologists recently looked at a bunch of studies measuring the accuracy of being able to predict someone else’s thoughts when going out of your way to understand their point of view. It wrote:

Although a large majority of pretest participants believed that perspective taking would systematically increase accuracy on these tasks, we failed to find any consistent evidence that it actually did so. If anything, perspective taking decreased accuracy overall while occasionally increasing confidence in judgment. Perspective taking reduced egocentric biases, but the information used in its place was not systematically more accurate.

This is why I’ll always think the young men who think good grades are for sissies and the Chinese businessmen offering deplorable working conditions are WRONG, even if they might argue back to me with just as much conviction. You have to live it to believe it.

So here’s the advice. And to avoid irony I hope this is broad enough to apply to most of us:

The few immutable truths of finance – the stuff no one argues about because there are right answers – are what matter most. But we hear about them the least, specifically because no one argues about them.

Spend most of your time contextualizing those truths within your own goals, needs and experiences, realizing that it’s OK if others disagree with your views and you disagree with theirs.

When you watch, listen, and read about other people’s views, the most important takeaways are insights into how people deal with risk and uncertainty, because those are the broad lessons that are likely to apply to the greatest number of people, including yourself.

Learning from others is a huge part of investing – every mistake has already been made and you can add years to your life learning from them vicariously. But most investment debates can and should be replaced by acknowledging that reasonable people can disagree because we’re all different and driven by things that are hard to quantify. The fun part of behavioral finance is learning about how flawed other people can be. The hard part is trying to figure out how flawed you are, and what makes sense to you but would seem crazy to others.