Part II: Collab x The Climate Crisis

In Part I, we covered why we believe there has never been a better time to start a company addressing the climate crisis. A core part of our hypothesis is: as climate technology expands to cover the entire economy (rather than just the energy sector), there is nearly unlimited upside.

While the massive scope of the opportunity is inspiring and energizing – there are so many ways founders can succeed – it’s also abstract.

For some, climate tech is synonymous with clean tech. Others limit their interest to software-based solutions. And then there are folks who would only work with businesses that prevent the climate crisis, and couldn’t touch an adaptation project.

Now, let’s offer some context for how Collaborative evaluates new businesses, and determines what is vs. isn’t in scope for our fund.

The first step of diligence is identifying the primary type of risk the business will face. While understanding potential challenges won’t get us to invest, it’s a good first screen to determine if a business is too risky for us to commit to. Plus, it sets up a more efficient decision-making process.

In general, we can categorize each business by one of the following risks:

-

Technical – The product hasn’t demonstrated comparable performance and price to the carbon-based technology it will replace

-

Business model – Demand for the product - in terms of willingness to pay and overall market size - is unproven

-

Regulatory – The product is more expensive or cumbersome than existing alternatives, and will require additional government incentives for users to adopt

A company is unlikely to be a fit for our model if it faces two or more of these.

And while we’re eager to see how startups will take advantage of upcoming policy changes under the Biden-Harris administration, we are not actively investing in companies that depend on significant regulatory changes to scale.

1) Technical Risk

When evaluating companies developing a new technology, we apply an industry/sector lens. We expect these companies to displace a widespread, carbon-based technology. And understanding the performance and price requirements of key buyers, and how they interact with established supply chains gives us a benchmark by which to measure the potential impact of the breakthrough.

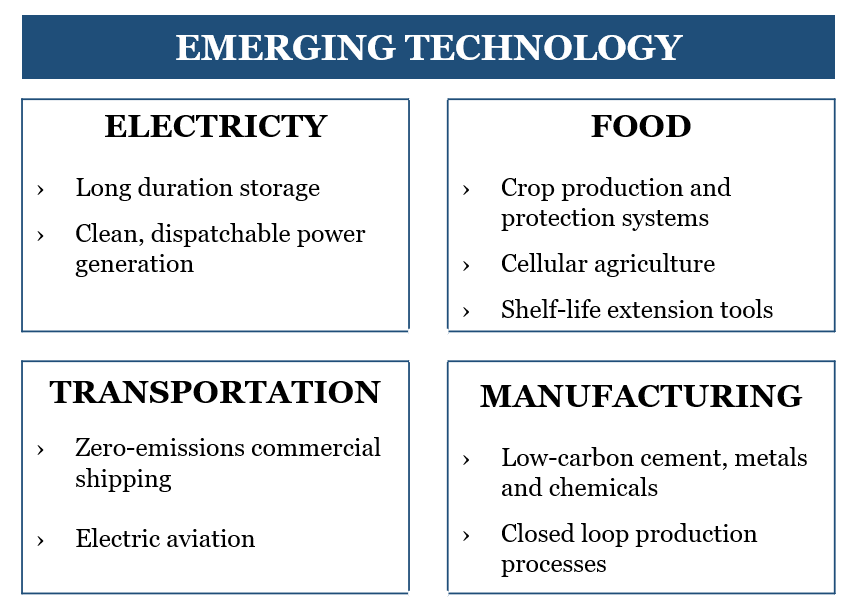

We organize our work into four sectors: electricity, food and agriculture, transportation, and manufacturing. Each of these has large sources of emissions that are unaddressed by existing technologies and benefit from increasing market pressures to adopt low-carbon technologies in the next decade.

Electricity

As wind and solar have become more economical and reliable, the lack of cost-effective storage is now one of the biggest barriers to advancing the share of renewables on the grid. We’re eager to support distributed and utility-scale long-duration storage projects, as well as alternative energy sources (e.g., geothermal, nuclear, etc.) that can fill the gap in electricity needs.

Transportation

Electrification of passenger vehicles, made possible by the rapid decline in the cost of batteries, is one of the great success stories from the last cleantech boom. We expect EVs to go mainstream as major manufacturers make the switch and EV charging infrastructure reaches maturity. We still have a long way to go when it comes to electrifying air travel and shipping. The battery technologies we have today aren’t sufficient to completely decarbonize these cases – meanwhile, emissions are growing with globalization. Going forward, we’re excited about the role that clean hydrogen can play in powering zero emission travel.

Food & Agriculture

A lot of the work to decarbonize food and agriculture has focused on limiting our dependency on animal-based agriculture. While cultivating animals for food requires more land and carbon than most other food production, we’ll need to rework our entire food system to limit emissions, land use, water withdrawal and food waste. With advances in synthetic biology, we see huge potential for engineering crops that require fewer resources and are more resilient to weather variability, biofertilizers that replace synthetic nitrogen, new protein sources, and shelf-life extension technologies that limit waste.

Manufacturing

So far, we’ve seen large industrial and manufacturing players as the most resistant to low-carbon technologies. They’re not subject to the same consumer pressure as food or transportation companies. Plus, unlike in energy where performance of the end product – electricity – is standard and known, new technologies that alter the formulation of materials introduce risk that is hard for most stakeholders to tolerate. However, we’re encouraged by the success of startups like Solugen – which can compete on cost and production efficiency.

2) Business Model Risk

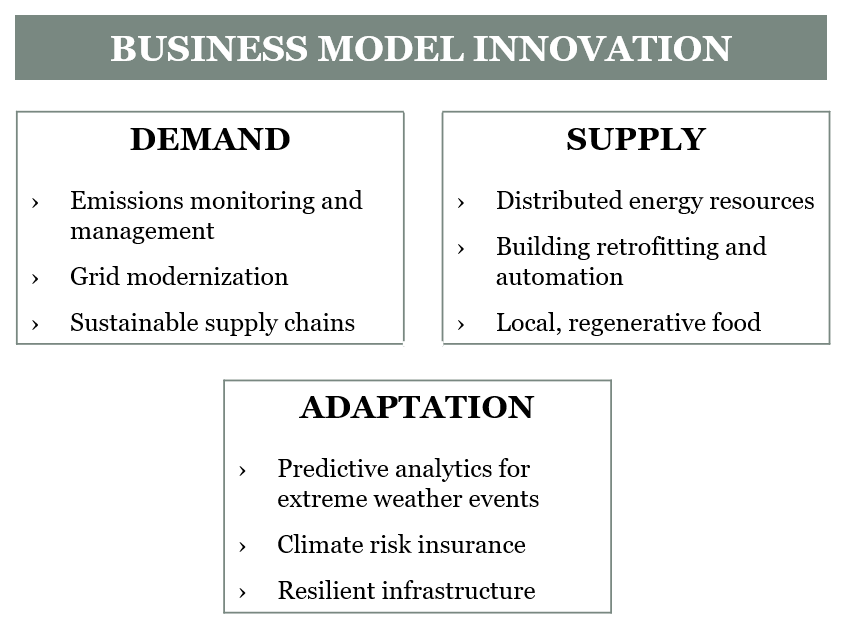

Many of the technologies that we need to decarbonize and prevent future emissions already exist, but adoption has lagged behind technical breakthroughs. Novel business models that deliver cheap supply or capture increased demand will unlock new markets for proven low-carbon technologies.

The same is true for many adaptation challenges. As our physical and financial exposure to climate change increases, we can apply existing sensing and ML technologies to measure, predict, and insure against volatile environmental conditions.

A relatively small part of the first cleantech wave, businesses in this category have generated many of the best returns thus far. On the demand side, companies like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods recognized a growing appetite for plant-based food, and delivered a solution for non-vegan consumers looking for a healthier, more eco-friendly option. On the supply side, Nest gave us the first smart thermostat – offering consumers the convenience and savings of energy-efficient heating and cooling without even thinking about it.

Going forward, we’re eager to see new platforms that support corporate investment in low-carbon technologies by helping them monitor and manage the full scope of their emissions, and invest in decarbonizing their supply chains and procurement practices. A great example of this is LevelTen which offers large energy buyers the tools to compare and purchase the best renewable options for their needs.

Finally, regardless of how quickly we can deploy these low-carbon technologies, we will inevitably face increased exposure to climate risk. We see a big opportunity for businesses that help individuals, enterprises, and governments assess and prepare for severe climate impacts. As more scalable data collection comes online, we’ll be looking for novel risk analytics platforms that enable better-priced insurance products and inform investments in resilient infrastructure.

This framework is a work in progress. We are always iterating and looking for better ways to efficiently evaluate new opportunities. And I hope that in six months some of these themes will be out of date. Until then, if you’re working on a breakthrough technology or novel business model that can rapidly accelerate decarbonization and adaptation, we’d love to learn from you.