You Better Love This

Something stupid you can stick with will probably outperform something smart that you’ll burn out on.

The investing strategy you should follow, research project you should undertake, or the book you should write doesn’t need to be related to what’s going on in the news. It doesn’t even need to be what’s likely to work the best.

It should just be whatever you’re interested in.

If you view “do what you love” as a guide to a happier life, it sounds like empty fortune cookie advice. If you view it as the thing providing the endurance necessary to put the quantifiable odds of success in your favor, you realize it should be the most important part of any strategy.

Getting anything to work requires giving it an appropriate amount of time. Giving it time requires not getting bored or burning out. Not getting bored or burning out requires that you actually love what you’re doing, because that’s when the hard parts become manageable.

Invest in a promising company you don’t care about, and you might enjoy it when everything’s going well. But when the tide inevitably turns you’re suddenly losing money on something you’re not interested in. It’s a double burden, and the path of least resistance is to move onto something else. But if you’re passionate about the company to begin with – you love the mission, the product, the team, the science, whatever – the inevitable down times when you’re losing money or the company needs help are blunted by the fact that at least feel like you’re part of something meaningful, which is fuel to stop you from giving up and moving on.

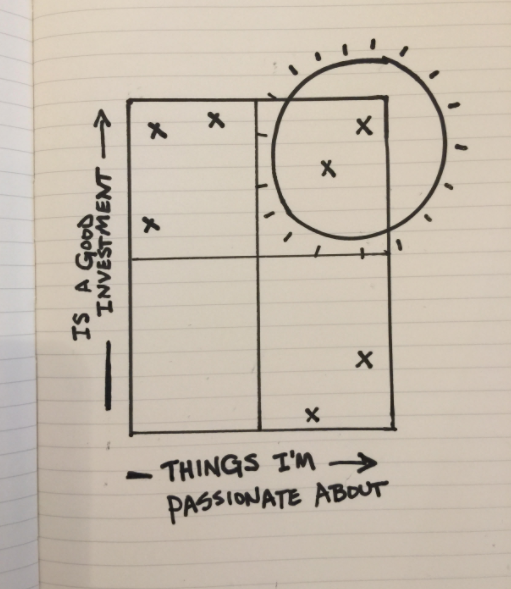

Craig illustrates it like this:

This might seem soft, like a path to becoming emotionally attached to investments and believing stories over facts.

It shouldn’t.

There are few financial variables more correlated to performance than commitment to a strategy during its lean years – both the amount of performance and the odds of capturing it over a given period of time. The historical odds of making money in U.S. markets are 50/50 over one-day periods, 68% in one-year periods, 88% in 10-year periods, and (so far) 100% in 20 year periods. Anything that keeps you in the game has a quantifiable advantage, and time horizon is so powerful in investing that the ill-conceived portfolio you love may be better than the perfect one that bores you and that you’ll abandon the moment it’s out of favor. It’s almost a badge of honor for investors to claim they’re emotionless about their investments. But if lacking emotions about your strategy or holdings increases the odds you’ll walk away from them when they become difficult, what looks like rational thinking becomes a liability. The counterintuitive truth to compounding is that decent growth sustained for the longest period of time is superior to huge growth that can’t or won’t be maintained.

Same in careers. A job that pays $100,000 a year in a field you love will probably be more financially rewarding than one paying $150,000 in a field you don’t, because the job you’re only in for the big paycheck increases the odds you’ll burn out or get bored and need to find a new calling. What is the quit rate among lawyers and investment bankers? I don’t know, but it has to be huge. And both can be great experiences with transferable skills. But if you focus on the money – and many lawyers and investment bankers do – I wonder how many would be better off just starting in a field they love and won’t burn out on, letting their career blossom as contacts and niche skills compound.

The trick is getting the hard parts – the down years, the failed product launches, the emails asking for help – to feel like fees instead of fines. Fees are something you’re happy to pay because you know you’re getting something greater in return. Fines are things you should avoid, a feeling that you’re being punished and need to do things differently.

Whatever you’re doing, you better love it.