Corona Panic

It’s OK to not have an opinion on topics you don’t know anything about. And I don’t know anything about coronaviruses. But I have a few thoughts about how people think about risk.

We should remember Daniel Kahneman’s advice: “Human beings cannot comprehend very large or very small numbers. It would be useful for us to acknowledge that fact.”

This is the first global crisis in the social media age. What we’ve learned from social media in the last decade is that 1) information spreads fast, 2) false information spreads fastest because it’s more sensational, and 3) tribal identities are heightened when debates take place online vs. in person, so healthy debate quickly descends to a my-team-versus-yours battle. FDR said, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” in an era when the only information source was a morning newspaper, edited and fact-checked by professionals, written by journalists who weren’t motivated by likes, retweets, or paid per click.

Uncertainty amid danger feels awful. So it’s comforting to have strong opinions even if you have no idea what you’re talking about, because shrugging your shoulders feels reckless when the stakes are high. Complex things are always uncertain, uncertainty feels dangerous, and having an answer makes danger feel reduced. We want firm answers when things are the most uncertain, which is when firm answers don’t really exist.

We’re not mentally prepared to think about widespread risk. Here’s German psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer in his book Risk Savvy:

People aren’t stupid. The problem is that our educational system has an amazing blind spot concerning risk literacy. We teach our children the mathematics of certainty—geometry and trigonometry—but not the mathematics of uncertainty, statistical thinking. And we teach our children biology but not the psychology that shapes their fears and desires. Even experts, shockingly, are not trained how to communicate risks to the public in an understandable way.

Risk has three parts: The odds you will get hit, the average consequences of getting hit, and the tail-end consequences of getting hit. How people respond to risk is heavily influenced by the tail-end consequences of getting hit, even if it’s the least probable outcome.

This is a multi-disciplinary problem. It’s part biology, part statistics, part politics, part sociology, part psychology, etc. No single person has all the answers.

During the financial crisis it was clear that specific people would be hurt (those heavy in debt) and specific people would be fine (no debt, lots of cash). Viruses are different because they don’t care about how much money you make. Healthcare is skewed by income, but the equality in catching the coronavrius brings a level of fear to groups of people who aren’t used to having to be scared.

“Wash your hands” might be the best advice at this point. That’s what I hear, at least. But it’s too simple for some people to take seriously. The idea that complex problems can benefit from simple solutions isn’t intuitive.

In a bad recession you might see sales down, say, 3%, or maybe 20% in some sectors if it’s really ugly. Macau casino revenue was down 87% last month. I don’t know what that means over the next year, but this is not your typical slowdown.

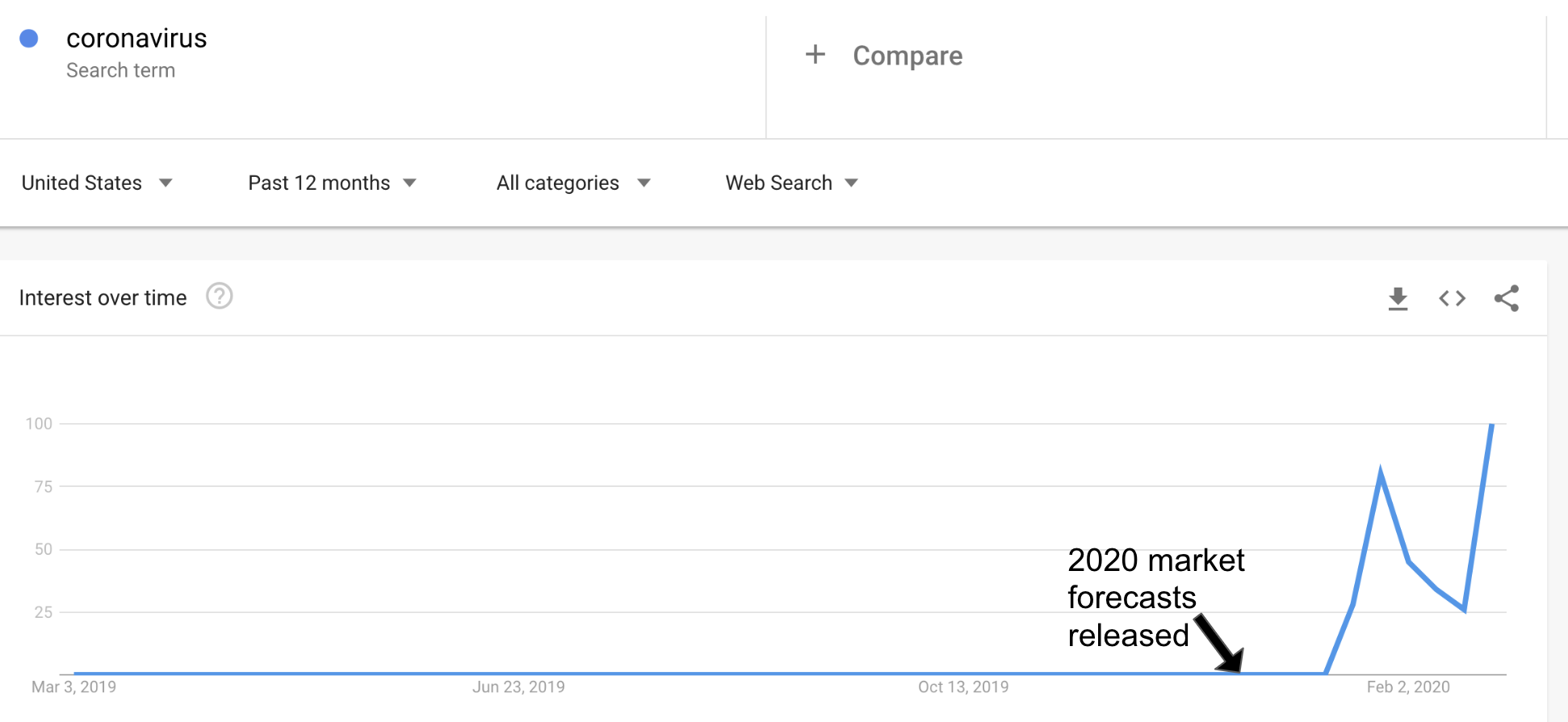

Risk is what you don’t see coming. Here are Google search trends for “coronavirus.” This is why forecasting is hard: